The holidays are upon us and North American triathletes are many weeks (if not pounds) into the off-season. While some athletes are reliving their racing exploits over a glass of eggnog and peacefully slipping into a Christmas cookie coma, others are already looking ahead to next season.

Laying out your training and racing plans for the coming season can help you stay motivated, enthusiastic and on track over the off-season, and sharing your plans with others adds a level of accountability. Knowing when to pour it on and when to back off in training—and having confidence in these decisions—is critical to achieving your best results.

Advance planning is not only a performance enhancer, but also a way to savour the pleasure and excitement of the coming season. Planning, anticipating and working towards a rewarding experience is the practice of delaying gratification, an ability associated with health, wealth and happiness (e.g. 1, 2, 3).

|

| Failing to plan is planning to fail. |

I have to admit that planning my season in advance is a first for me. In the past, I’ve flown by the seat of my pants, training hard when I felt good, moping around when I felt bad and racing on the spur of the moment. This year, with the help of Richard Pady of Healthy Results, I began to appreciate that planning and periodization are essential for consistency, longevity and high performance. The time had come for a less amateurish approach.

In this post, I’ll outline the approach I used to map out my season. It borrows from the Triathlete’s Training Bible by Joe Friel (a recommended read), but it is condensed for easy reading and includes some of my thoughts.

This post is not intended to be a comprehensive guide addressing all the subtleties of planning and periodization. That can be a tricky process for even the most experienced athletes and coaches. My aim is to provide a quick-start guide that will at least get you thinking about the upcoming season.

A Quick Guide to Planning a Race Season

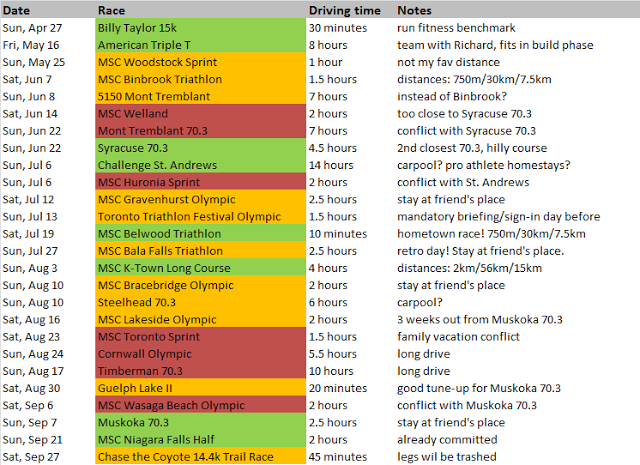

Step 1. Make a list of all the races over the coming season that appeal to you. Include key information for each event: date, distance, travel required and any other relevant details (e.g. entry fees, accommodations, competitors, schedule conflicts, championships, qualifying spots, course descriptions, prizes, etc.). Don’t worry if it’s a long list!

Step 2. Review your list and sort the events based on how well they align with your goals, strengths, schedule, location, budget, and other factors. Based on these criteria, decide which races are a good fit for you then colour code them like this:

- Green: Races you will almost certainly do. Add these to your calendar.

- Yellow: Races you may do. Pencil these into your calender.

- Red: Races you will probably not do. Scratch these off your list.

The number of green/yellow races should reflect the amount of time, energy and money you can throw at the sport, as well as your past racing experience. Some people can race every weekend for months, while others would risk burnout, injury, bankruptcy or divorce/breakup with such an ambitious schedule. Be realistic.

|

| Step 2: Identify races that are a good fit for you and colour code them. Green = definitely, yellow = maybe, red = probably not. |

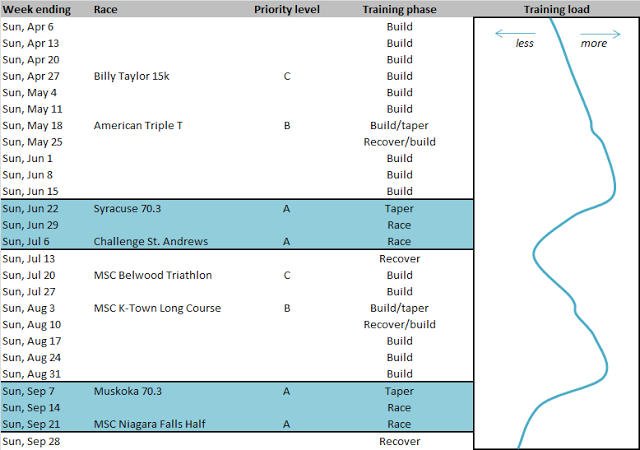

Step 3. Assign a priority level to each race based on how important a good performance at that event is to you.

- A-priority races: These are important races that you really want to nail. Your training is structured to create peak form and fitness for these events, including a build period and a full taper leading into the race and a recovery period following. Only designate a small number of A races, separated by at least a month. Two or more A races over a period of a couple weeks count as one A racing block.

- B-priority races: These are secondary priorities, usually scheduled during the build up to A races. Plan on an abbreviated taper and recovery period, but otherwise keep the impact on your training to a minimum. Choose a few of these during your season.

- C-priority races: These are glorified training days. Don’t pull any punches in training the week before. Jump in as many of these as you feel like as long as they don’t interfere with training objectives or recovery. Also don’t hesitate to scratch C races for any reason.

|

| Step 3: Assign a priority level to each race. My shortlist for 2014 has four A races grouped in two blocks. |

Step 4. Divide your season into phases with distinct aims in terms of training, racing and recovering. Think of this as a broad-strokes overview of your training. At this point, the idea isn’t to hammer out the day-to-day details of your training; that can be done at a later date. Here’s a very brief description of four basic phases:

- Build: The serious work happens during this phase. It starts a few months out from your A race(s) and typically features a gradual progression in training load (volume and/or intensity). Schedule B and C priority races during this phase.

- Taper: This phase allows your body to assimilate the work from the build phase and shed fatigue in order to maximize fitness and form. The classic doctrine for tapering is reduce volume, maintain intensity, and maintain frequency of workouts, but there’s no one-size-fits-all formula. Finding your ideal taper is a trial and error process and, for me, no two tapers are ever exactly the same.

- Race: This is the brief period during which you intend to achieve peak fitness and form for A races. Training load is reduced compared to the build phase, with hard efforts coming from races and a handful key training sessions. Restrict this phase to a couple weeks since you can only truly peak for a brief window of time before recovering and rebuilding.

- Recover: Plan a recovery phase of at least one week after each race phase. This doesn’t have to be time completely off training, but don’t schedule any races and keep your training load well below your build phase.

Your A races dictate the structure of your season. Everything else follows from these. Scratch any races that interfere with your ability to peak for the A races. Hopefully you can slot in all your “green” races and many of your “yellow” ones. If not, you may need to go back and refine your A/B/C designations until everything jives.

Reflect on previous seasons. Think about your best performances. What led up to them? What worked and what didn’t? What triggered your peak(s)? How can you apply this knowledge to the coming season?

Successfully timing a peak is no mean feat, and is something that the top athletes in the world and their coaches routinely blow. Triathletes, in particular, have a tough job since they are attempting to simultaneously achieve peaks in three sports, which won’t necessarily coincide. It’s not uncommon for athletes to round into great form before or after it was intended.

For example, I was surprised to discover my peak bike fitness of the season after my last races in September. In retrospect, it was anything but random. A month-long reduction in training load punctuated by a few race efforts and was evidently a winning formula, an observation I’ve filed away for this season.

If you find yourself with unexpectedly awesome form/fitness and an open schedule, consider jumping in an unplanned race. Sometimes it pays to “strike while the iron is hot”, but don’t let spur-of-the-moment decisions interfere with the master plan.

Finally, remember that no plan is carved in stone. The most successful athlete isn’t the one that attempts to execute their plan to a tee, but the one that best adapts it to inevitable and unforeseen circumstances (illness, injury, family, work, etc.).

Case Study: My 2014 Season

Let’s take a quick look at my 2014 plan to illustrate some of the concepts discussed above. The season is anchored by two A racing blocks, one in late June/early July and one in September. Both feature two half iron A races separated by two weeks and sandwiched between taper and recovery phases. During these two racing blocks, the emphasis will be on racing, recovering and staying sharp, not on building/maintaining fitness.

Two B race serve important purposes. American Triple T in May is a unique triathlon stage race (a Sprint, two Olympics and a Half Iron over 3 days) that will be a killer training weekend one month out from my first A race. The second B race, MSC K-Town Long Course in August, will be an opportunity to gauge fitness and identify areas for improvement leading into the final A races of the season.

I’ve penciled in a few C-priority races, but I generally won’t commit to these until the week before. These will act as hard training days and “tune-ups” in the build up to the A racing blocks.

A first for me is to schedule a week-long midseason break after the first racing block. In previous years, I’ve crashed at some point during the season, most notably in July 2013 when overreaching led to a bout of extreme fatigue that forced me to scratch the National Championships, my intended A race! That experience reinforced the importance of being proactive about recovery. Like most of you, I’m happiest when I’m training hard, but a little voluntary downtime sure beats a lot more compulsory downtime (think: “a stitch in time saves nine”). A midseason break should prepare me to build up to a second peak in September.

Questions or comments? Please join the discussion about this post on Facebook or Twitter.